Plants use engineering principles to push through hard soil

26.11.2025 17:01:00 CET | Københavns Universitet | Press release

An international research team led by the University of Copenhagen, Shanghai Jiao Tong University and the University of Nottingham has discovered how plant roots penetrate compacted soil by deploying a well-known engineering principle. The finding could have major implications for future crop development at a time when pressure on agricultural land is increasing.

Across the globe, soil compaction is becoming an ever more serious challenge. Heavy vehicles and machinery in modern agriculture compress the soil to such an extent that crops struggle to grow. In many regions, the problem is aggravated by drought linked to climate change.

But plants may in fact be able to solve part of the problem themselves – with a little help from us. It is already known that when soil becomes dense and difficult to penetrate, plants can respond by thickening their roots. Until now, however, it has remained unclear how they manage this, beyond the fact that the plant hormone ethylene plays a key role.

Researchers from the University of Copenhagen, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, the University of Nottingham and partners have now pieced together the mechanism. Their results have been published in the prestigious journal Nature.

“Because we now understand how plants ‘tune’ their roots when they encounter compacted soil, we may prime them to do it more effectively,” says Staffan Persson, professor at the University of Copenhagen and senior author of the study.

A biological wedge in the soil

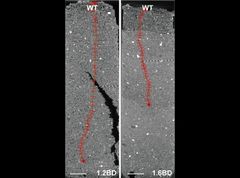

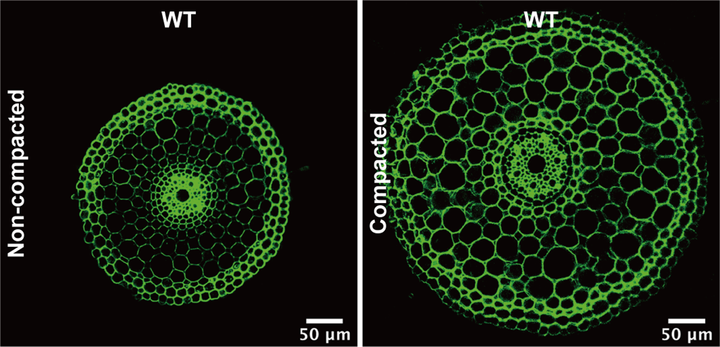

The team found that when soil is compacted and ethylene accumulates around the root, the hormone activates a gene called OsARF1. This gene reduces the production of cellulose in certain root cells, making the middle layer of the root thinner, softer and more flexible. This allows the cells to swell and the root to expand. At the same time, the outermost layer of the root (the epidermis) becomes thicker and stiffer.

“In other words, the root changes its structure in line with a basic engineering principle: the larger a pipe’s diameter and the stronger its outer wall, the better it can resist buckling when pushed into a compact material,” explains Bipin Pandey, senior author and associate professor at the University of Nottingham.

The combination of root swelling and a reinforced outer layer allows the root to act as a kind of biological wedge, easing its way down through the soil.

“It’s fascinating to see how plants draw on mechanical concepts familiar from construction and design to solve biological challenges,” says Staffan Persson.

Helping plants grow better in hard soil

The study also reveals how this mechanism can be amplified:

“Our results show that by increasing the levels of a specific protein – a transcription factor – the root becomes better able to penetrate compact soil. With this new knowledge, we can begin redesigning root architecture to cope more effectively with compacted soils. This opens new avenues in crop breeding,” says first author Jiao Zhang, postdoc at Shanghai Jiao Tong University.

Although the experiments were conducted in rice, the researchers believe the mechanism applies broadly across plant species. Parts of the same mechanism have also been identified in Arabidopsis, which is evolutionarily distant from rice.

“Our results could help develop crops that are better equipped to grow in soils compacted by agricultural machinery or climate-related drought. This will be crucial for future sustainable agriculture,” says professor and senior author Wanqi Liang from Shanghai Jiao Tong University.

The work also opens new opportunities in plant breeding more generally. The team has identified many additional transcription factors that appear to be key regulators of cellulose production – with far-reaching implications for plant form and structure. For example, it may become possible to design plants with different shapes, which could benefit certain crops.

“The transcription factors we’ve discovered are a goldmine for cell-wall biology. There’s more than enough here to keep me busy until retirement,” concludes Staffan Persson.

The study is the result of a collaboration between researchers in China, the UK, Japan, Argentina and Denmark, drawing on laboratory experiments, genetic analyses and advanced microscopy.

*

WHAT THE RESEARCHERS FOUND

- When soil becomes compacted, the plant hormone ethylene accumulates around the roots, triggering a chain reaction that alters root structure.

- Ethylene activates the gene OsARF1 in the root cortex (the middle layer), reducing production of cellulose – a key cell-wall component.

- Lower cellulose levels make cortex cell walls thinner and more flexible, allowing cells to swell and the root to expand.

- Meanwhile, the epidermis (the outer root layer) becomes thicker and more robust. The combination of a soft cortex and a strong epidermis helps roots push through hard soil.

ABOUT THE STUDY

- The research article is published in Nature.

- Contributing institutions include Shanghai Jiao Tong University; the University of Nottingham; Universidad Argentina de la Empresa; the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology; Zhejiang University; Duke University; Ludwig Maximilian University; and the University of Copenhagen.

Keywords

Contacts

Staffan Persson

Professor

Department of Plant and Environmental Science

University of Copenhagen

staffan.persson@plen.ku.dk

+45 35 32 13 52

Maria Hornbek

Communications Officer

UCPH Communication

University of Copenhagen

maho@adm.ku.dk

+45 22 95 42 83

Images

Links

Subscribe to releases from Københavns Universitet

Subscribe to all the latest releases from Københavns Universitet by registering your e-mail address below. You can unsubscribe at any time.

Latest releases from Københavns Universitet

Børn med dårlig tandsundhed har oftere hjerte-kar-sygdomme som voksne2.3.2026 07:00:00 CET | Pressemeddelelse

Huller i tænderne og svær tandkødsbetændelse i barndommen kobles sammen med markant højere forekomst af hjertestop, hjerneblødning og åreforkalkning i voksenlivet, viser nyt studie fra Københavns Universitet.

Heste fløjter og synger, når de vrinsker23.2.2026 05:00:00 CET | Pressemeddelelse

Ny forskning fra Københavns Universitet viser, at et hestevrinsk er mere komplekst end som så. Opdagelsen bryder med tidligere antagelser om det store pattedyr og kaster nyt lys over, hvordan heste kommunikerer. Et forskningsområde, der trods 4.000 års domesticering stadig er fyldt med ubesvarede spørgsmål.

Ny viden om Nordeuropas radiator: Vulkanudbrud i fortiden kan have skubbet havstrøm mod kollaps17.2.2026 10:59:19 CET | Pressemeddelelse

Ny forskning fra Københavns Universitet peger på, at vulkanudbrud under istiden kan have udløst pludselige klimaskift ved at forstyrre den Atlantiske havcirkulation (AMOC) og at temperaturen herefter kunne svinge mellem varme og kulde i tusindvis af år. Studiet bidrager med nye brikker til forståelsen af, hvad der kan få Nordeuropas radiator til at gå ned.

Hvor fandt stenalderens første bønder egentlig deres planter? Nyt studie giver svar13.2.2026 10:05:51 CET | Pressemeddelelse

Ved hjælp af avancerede maskinlærings- og klimamodeller har forskere vist, at forfædrene til afgrøder som hvede, byg og rug sandsynligvis var langt mindre udbredte i Mellemøsten for 12.000 år siden, end man hidtil har troet. Det kan betyde, at kultiveringen af de første planter og dermed landbruget opstod andre steder end hidtil antaget.

Når krisen kradser, står Danmarks frivillige klar11.2.2026 13:25:56 CET | Pressemeddelelse

En del af befolkningen står parat til at træde til, når der er krise og andre har brug for hjælp. Disse mennesker udgør en slags civilt beredskab af frivillige, mener KU-forskere fra Sociologisk Institut. Men det er ikke nødvendigvis de samme frivillige, du kender fra foreningslivet.

In our pressroom you can read all our latest releases, find our press contacts, images, documents and other relevant information about us.

Visit our pressroom